Dedicated to Mark Carter – who never passed the buck, even when the cards were stacked against us.

If you feel like you don’t really have much say at work – you’re probably right. Here’s how to start making a real impact on your day-to-day reality.

I’d make a terrible poker player. I have one of those faces that come with subtitles – you can read me like an open book (most of the day it’s an action-packed firefighter drama, around lunchtime something closer to “1001 Microwave Meals”). Still, one of the most important rules I follow at work comes straight from poker. “The Buck Stops Here” – an approach made famous by US President Harry Truman ❶ – puts an end to endless back-and-forths.

Who’s supposed to make the call? Why is it on you again? What happens if you don’t? In this week’s Memo you’ll learn why dragging issues at work are most likely your fault – and how you can finally put a stop to them.

Passing the Buck

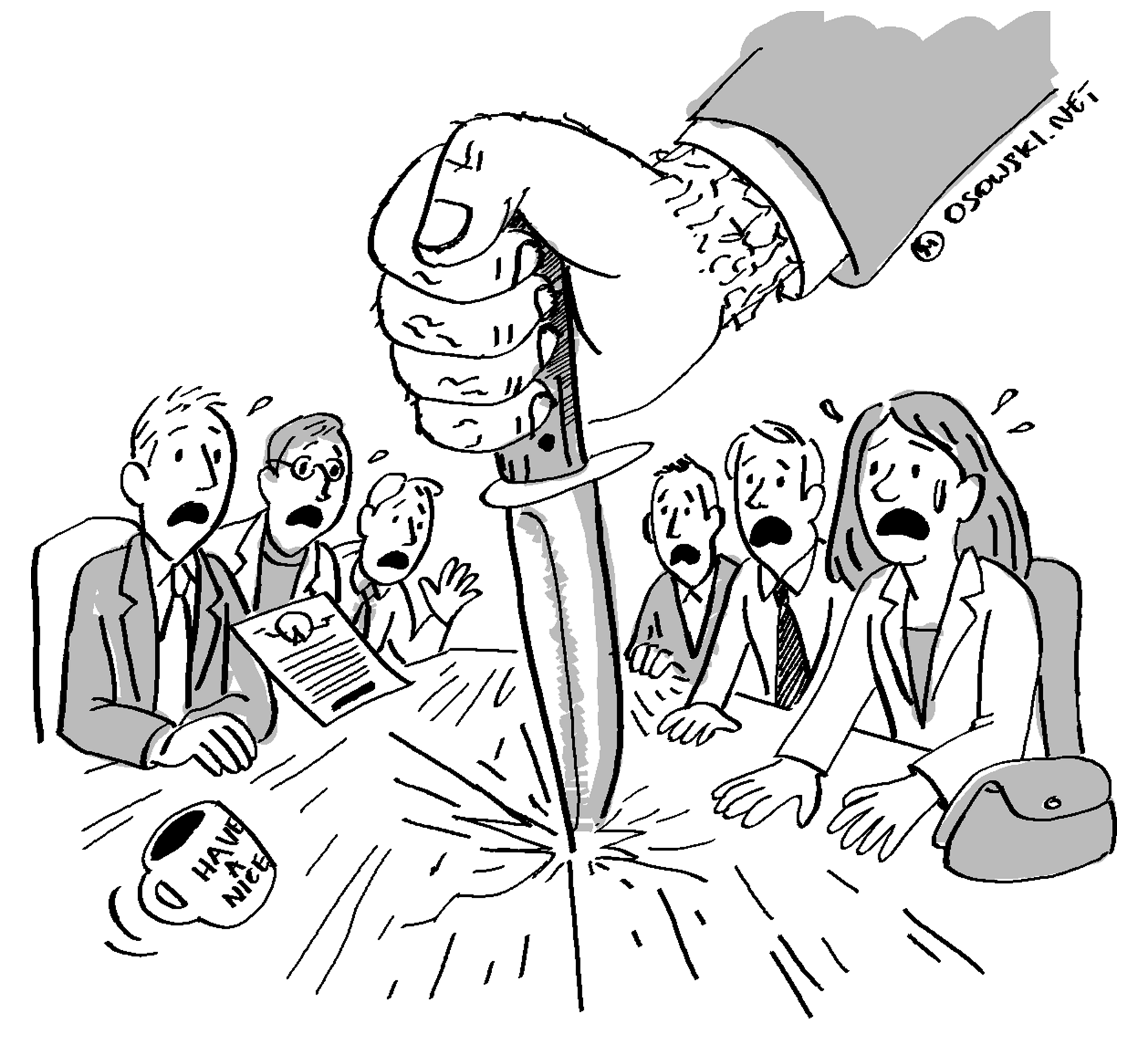

In the Wild West, poker-playing cowboys marked the one who had to shuffle the cards by sticking a knife into the table next to him. A knife with a deer-antler handle, the so-called “buckhorn.” To keep it fair, each round a different player shuffled, and the knife was passed along. Over time, the phrase “passing the buck” stuck as shorthand for shifting responsibility to someone else ➋. A move our coworkers still use all too often – though with a bit more respect for office furniture.

The problem of passing responsibility shows up most clearly in the difficulties companies face when making decisions. Managers in a typical large organization spend 37% of their time just trying to make one. More than half of that time is wasted ❸. In the end, fewer than half of decisions are made on time ❹. Sounds familiar? No surprise there. McKinsey reports that the average Fortune 500 company today loses as many as 530,000 workdays to inefficient decision-making – that’s about $250 million in labor costs down the drain every year ❺.

A hint at the causes comes from the main factors driving decision delays:

- organization size – companies with up to 10 employees close deals in an average of 38 days, while those with over 10,000 employees take 185 ❻;

- number of stakeholders – from available studies we can (in savage simplification) conclude that every additional person involved in an organization-wide decision extends the time to reach it by 1 month ❼.

6 Ways to Avoid Decisions

Making decisions sucks. The person making them risks professional and financial consequences (especially if they’re a board member), puts their reputation on the line, and on top of that takes on a mental burden (so-called “decision fatigue”) so heavy it can even lead to earlier burnout ❽.

People aren’t stupid, so they avoid the guilt, stress, and risks that come with making decisions whenever they can. Of course, they rarely do it openly – either in front of others or even to themselves. Which is why it usually takes the shape of one of the six covert tactics :

- Bullshit structures – committees and roles without power or resources, overlapping responsibilities between multiple people (e.g. “Chapter Lead” and “Team Lead”), or double accountability (e.g. being both a PM and a program manager for something else) – all serve to create the illusion that a problem has an owner or that the organization is actually addressing it.

- Analysis paralysis – drowning in analyses, data, and ever-multiplying options prevents a decision from being made in reasonable time. Instead of actually reducing risk, it causes delays and increases the costs of alternative choices.

- Procrastination – postponing decisions, often by raising new doubts at the end of what seemed like a conclusive meeting, suggesting yet another person who should be consulted, and scheduling another meeting on the same topic.

- Consensus seeking – the extreme case being the Japanese practice of nemawashi ❷❺; this shows up as the attempt to get absolute agreement from everyone involved, which results in something closer to a wish-granting ritual or group therapy than effective management.

- Reversed (upward) delegation – living in the belief that absolutely every decision more complex than choosing between the urinal and the toilet bowl requires the CEO’s involvement – often justified in English by “That’s above my pay grade.”

- Bureaucratic cowardice – theatrical pseudo-oversight mechanisms such as multi-level approvals, demanding a “full business case” for any initiative, or the obligation to consult or inform far too many people ❾. These flourish in companies where every failure ends in humiliation or sanctions; they drive participants to depend on cover-your-ass rituals and produce a strong bystander effect ❿.

It’s almost certain you’ve already run into every one of the tricks listed above. Worse, it’s more than likely you’ve resorted to them yourself. Yes. You avoid decisions too. Interestingly: in the long run this drags you down more than the potential consequences of any decision you might make.

So yes, making decisions sucks. However, research shows that – over the long run – avoiding them can make you feel just as bad.

Why Stop a Buck?

We already know that decisions are an organizational nightmare on a global scale. After all, according to Bain & Company, companies lose 15–20% of their productivity every year because of inefficiencies in this area ⓫. But here it’s worth asking the fundamental question that has kept philosophers awake for centuries: “So what?” In the unlikely case of banalities like “that’s what you’re paid for” or “so the company doesn’t go under” not being convincing enough for you to engage more in making decisions, let’s take a look at what science says about the impact of decisions on you personally.

High demands from your environment combined with low control due to lack of decision-making power raise your stress levels, increase the risk of burnout, and harm your health ⓬. Chronic lack of influence breeds learned helplessness: apathy, resignation, and depressive symptoms ⓭. Low control also correlates with higher cortisol, worse sleep, and a greater risk of illness ⓮. Avoiding decisions amplifies long-term regret about inaction ⓯ and undermines your sense of meaning and agency in daily life ❷❻.

Meanwhile, cross-cultural research from 11 countries shows that making decisions builds a sense of autonomy ⓰, which in turn accounts for a full one-third of psychological well-being ❷❼. Every closed choice also strengthens our self-sufficiency ⓱. And self-sufficiency improves our health, measurably lowering the probability of the decision-maker dying within the next 18 months ⓲. On top of that, decisions made in the face of difficulties increase our mental resilience ❷❽ and give us a stronger sense of meaning and agency ❷❾.

That said – screw the $250 million in wasted labor costs Fortune 500 companies rack up every year. And screw the productivity drop tied to decision-making gridlock. The real point is: as humans, we make decisions so life has meaning and flavor. You deserve a say in what happens to the organization you dedicate a third of your day to. So let’s talk about all the fear-driven doubts our brains love to feed us to avoid doing exactly that.

How to Stop a Buck?

If making decisions came naturally to me, I wouldn’t need a rule dedicated to it, nor would I have so many thoughts circling around it. Humanity wouldn’t have invented those 6 ways of avoiding them, and sociologists – instead of cranking out 33 footnotes for this text – might finally settle whether people who actually like marzipan even exist(!?).

Meanwhile, the animal fear we often feel when faced with a decision is a real obstacle to making one. And since we’re talking about decisions, it usually shows up in the form of so-called “doubts” (aka ‘buts’). Here are 5 common doubts that often come up for me and for colleagues in my teams, along with approaches that can help resolve them. You don’t have to read them all. Pick the one – or ones – that came up for you at your last meeting and see whether the suggested approaches would bring you any closer to making a decision. If nothing rings a bell, jump to the next part.

But does this situation even require a decision?

- Default aggressive ❸⓿ – by default, choose action (a decision) rather than staying passive. Keep the initiative by addressing problems that come up in the discussion/meeting as long as they fall within your area of competence.

- Your body will often tell you that the situation calls for action. And most of the time it will also do everything it can to talk you out of it. Read the piece “Don’t Piss in Your Boots” to learn how you can turn this to your advantage.

But can I even make the decision in this case?

- The right to make a decision is rarely granted explicitly. More often, it follows from our responsibilities – if the company expects us to deliver a result, then it also empowers us to do whatever it takes to achieve it. And that includes making decisions. (If it doesn’t, your organization is acting irrationally and you need to escalate.)

- “The one the Jews come to for counsel is the rabbi.” ❸❶ – that’s a piece of wisdom from one of my favorite books. If you’ve been invited to a meeting and asked a question, it means that, in the eyes of the organizer and the group, you are the source of the decision on that matter.

- Granted, this is a last resort, but also keep in mind the resilience of your organization. If you overstepped your authority and made a decision that fell within my remit, you’d find out about it very quickly. Very directly. So don’t overdo the caution – act in line with your best judgment.

But what if I don’t know which option to choose?

- Tough choices are mostly those between similarly appealing options. Ruth Chang explained this brilliantly in a TED talk, which you can watch here.

So if you don’t know how to choose, you most likely lack enough differentiating data about the available options. There are two solutions: if you have the time and resources, get more information; if you don’t, you must make a discretionary decision carrying greater risk.

The ability to make discretionary, intuition-driven decisions is one reason AI won’t fully replace managers anytime soon – and an expression of personal freedom, without which we’d be slaves to data. Put your free will to work.

But what if my decision has negative consequences?

- Perfect. In the long run, it’s better to make the call and test the real value of your expertise than to keep your surroundings – and above all – yourself in the false belief that you are in the know.

Ultimately, only by making decisions and letting reality test them can we learn. Minimizing mistakes means improving decision quality, not avoiding decisions altogether. Trying to preserve authority or position by dodging verification is posturing, not caution.

As the modern American poet Obie Trice put it in his single “Wanna Know”: Hop out the car, catch the bus. At least you’ll be established as the man that you are. Any other approach is a ready recipe for impostor syndrome. - Enter: Jim Carrey. For me and several others who wrestled with the same doubt, Jim Carrey’s speech – excerpted here – was helpful.

Mr. Carrey talks about how our motivations in life boil down to two: negative (fear) and positive (love), and he explains why it’s not worth acting out of fear. - Also know this: the very fact that you made a decision – regardless of whether it was “right” – is a business advantage.

Data shows that decision speed itself has a positive effect on its quality ❸❷. Delaying that decision by even 5% would, as a rule, create a cost of delay far greater than any gain in quality ❷❷. So it’s good you didn’t wait.

It also matters that you didn’t escalate the decision upward – it’s frontline employees who hold, on average, 70% of the information critical for decision quality. The higher up you go, the worse it gets ❷❸.

By making the decision you kicked off another cycle of organizational learning, unlocked feedback, spared your team the opportunity costs of delay, and cut the costs of endless option-weighing. - It may also help to know that the negative consequences of your decision – especially if you work in a large organization – often have more to do with organizational culture than with the scale of the actual fuck-up you might cause.

Conservative organizations, e.g. in the public sector, promote risk avoidance by punishing failures harshly. Innovative companies actively reduce the subjective and reputational cost of mistakes by normalizing them. That’s how Amazon pitches itself to potential hires as “the best place in the world to fail” ❷❹, and, in line with Working Backwards, even hands out awards for ambitious ideas that ended in failure. Spotify does the same (“fail-fikas,” “fail wall”), as does Netflix EMEA (“honourable failure”).

If your company allows for this – focus on reality, not politics. If not – consider changing companies.

But what if nobody listens to me/my decision doesn’t stick?

- Making a decision is nothing more than moving from problem to solution. In other words – if your decision unblocked the work, it was effective. The simplest way to guarantee that effectiveness is to personally take the first step toward carrying it out. You don’t need to execute it fully – often it’s enough just to get it started.

- Disagree and commit – some people may not agree with your decision, but they have no right to sabotage it.

Every sane decision-maker should make full use of the team’s potential when weighing options (see more in “Every Pro Has Its Cons”). But once an option is chosen, every person involved is obliged to contribute to execution as if they were its supporter – that’s part of their employment contract.

Which means that even if one of your colleagues opposed the decision you made, they have no right to reopen the discussion just to finally “get their way,” nor to stand off to the side with folded arms and a face that screams “I’m not playing anymore.” Reminder: companies aren’t democracies, they’re dictatorships with fruit baskets on Thursdays and a sole working printer.

The first to raise this – albeit in a much more civilized form than mine – was Andy Grove in his classic High Output Management. ❷❶ His words were later echoed by Jeff Bezos in his 2016 shareholder letter. ⓴

If, after considering both their contractual obligations and the words of these authorities, someone still refuses to work on delivering the option you chose, maybe they just don’t want to work at all? Discuss it face to face, before their stance drags down the team’s morale and undermines the effectiveness of your decision. - Consider NAG – one of the dark patterns related to decision making described in the next paragraph.

Where the Buck Shouldn’t Stop

So let’s assume for a moment that, moved by the greater good (the company’s) and your own, and having shed all doubts, you’ve become a confident decision-maker. As with anything, though, it’s not worth going overboard. While management literature lists about 9 types of problems that can stem from overzealous decision-making, let’s focus on the 3 most important ones I’d ask you to avoid:

- Reversed delegation and lower decision quality – decisions are only as good as the information behind them. And the most information is always closest to the problem. For instance: if it’s a machine breakdown, the person with the most insight is the worker standing right next to that machine, seeing what isn’t working. If you or your company have trained that worker that it’s not worth it – or too risky – to decide to stop the machine, they’ll waste time calling you for the decision. That decision then gets made by someone who may have never even laid eyes on the machine, and is far more likely to be wrong. That’s exactly why Toyota uses the Andon cord ⓳, and why you and your company should make sure decision-making is placed as close to the problem as possible.

- Micromanagement – petty authoritarianism. It shows a failure to understand the difference between strategy and the tactics used to carry it out. It happens when, instead of limiting yourself to a directional decision, you take it a step further and try to dictate the fine details of execution – details you won’t be executing yourself. This can also be triggered by your coworkers through reversed delegation, when – due to company culture or personal preferences – it’s easier for them to dump responsibility on a peer or their boss. You’ll find more on micromanagement in “Repeating Is Micromanagement” (coming soon).

- No Authority Gauntlet (NAG) – a phenomenon aptly described by Ashwani Badlani ❸❸. It happens when the company gives you a task without the resources to deliver it, or when your decisions go beyond your real scope of authority. The result: in order to reach the goal, you depend on people who, since they report to other managers, will always prioritize their bosses’ requests over yours – even while they show up to your meetings and nod along at the wisdom of your directions. In the end, nothing actually gets delivered, and your intended goal cannot be achieved.

The Buck Stops With You

Put simply, knowledge work is about making decisions. You already know that avoiding them causes massive losses for the global economy, turns into a little circus, and ultimately harms your health. I hope the approaches to resolving common doubts will help you make them. Just be careful not to fall into one of the dark patterns described here.

Whether you’re a manager or a specialist, your company needs clear, straightforward decisions that move things forward. Not just from you, but from all your colleagues too. Your firm “The Buck Stops Here” will deliver double value – as the engine for your own work and as a good example for others. Along the way, it will also test how much your expertise is really worth. Now good luck with that buck!

Sources & side notes

As this time the text features 33 sources and side notes, they are available on a separate, dedicated page.