What do teamwork and dancing have in common? Here’s why it’s worth it to challenge and be challenged – and where to find the kind of healthy pressure at work that keeps you from going soft.

"A subordinate should in the presence of their superior look pitiful and foolish, so as not to embarrass the superior with their grasp of the matter" – so allegedly decreed Tsar Peter the Great (1672–1725) ❶.

Today, more than 300 years later, such an approach to workplace relations seems both pathetic and laughable. But is it though?

I’ve seen a sentiment much like the Tsar’s not only in more than one modern-day boss, but also – surprisingly – in some subordinates. Its equivalent between equals is nodding along to colleagues’ ideas in the names of the commandments “so that it may be pleasant” and “so that no one may be offended.”

Below you’ll read about why and when it’s worth saying “no” at work – to everyone. How to deliver a solid “no,” even to your boss. How to take a “no” on the chin in such a way that it won’t be the last honest “no” you’ll ever get to hear.

Cuddlelands

Let’s be honest – a sense of security is one of the most important aspects of work. It has a few basic elements, among them:

– physical (health) safety,

– job stability,

– fair accountability, and

– a friendly atmosphere. ❷

A friendly atmosphere! Naturally, since we were all raised on Winnie-the-Pooh and Care Bears, we’d like everything to feel nice everywhere. Always. At work, this mostly shows up as an aversion to questioning the attitudes of our coworkers or the quality of their results. After all, why risk a relationship when “nobody’s paying me for that” and “it’s not worth stepping on anyone’s toes”?

That’s why what you often see is a you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours kind of setup. And in the jungle of perks offered by high-paying industries, it’s sometimes harder to find an effective team than a tight-knit one. This is how whole workplaces emerge where a friendly atmosphere has completely replaced accountability – which my former colleague half-jokingly dubbed Cuddlelands.

Backbone Breakers

Even though the age of lords and peasants is long gone, some of us still work in companies where job stability and fair accountability depend only on staying in good favor with the boss. If you’re in such a place, then in terms of standards and organizational culture, the only thing separating your company from a medieval manor is the guarantee of physical safety — in other words, at least no one beats you there.

There are bosses so fragile in their self-esteem they can’t bear the slightest opposition from subordinates. My colleague, coach Eligiusz Kobyłkiewicz, presented a fantastic case study of this some time ago, titled The Reversible Castration of Managers — about an infallible director who stamped out all resistance and independent thought in his team, only to collapse under the burden of having to make even the simplest decisions on their behalf.

On the other side, I’ve also met employees with a naturally servile style. The kind who — probably in the name of proactively protecting their job stability and “fair” accountability — hang on their manager’s every word, happily rushing to carry out even the most exotic of their ideas.

Alongside the “Cuddlelands,” this is how teams arise whose backbone has been broken by an insecure boss and others that are spontaneously spineless. Together they make up the three horsemen of the friendly atmosphere in modern workplaces.

Apply the Pressure

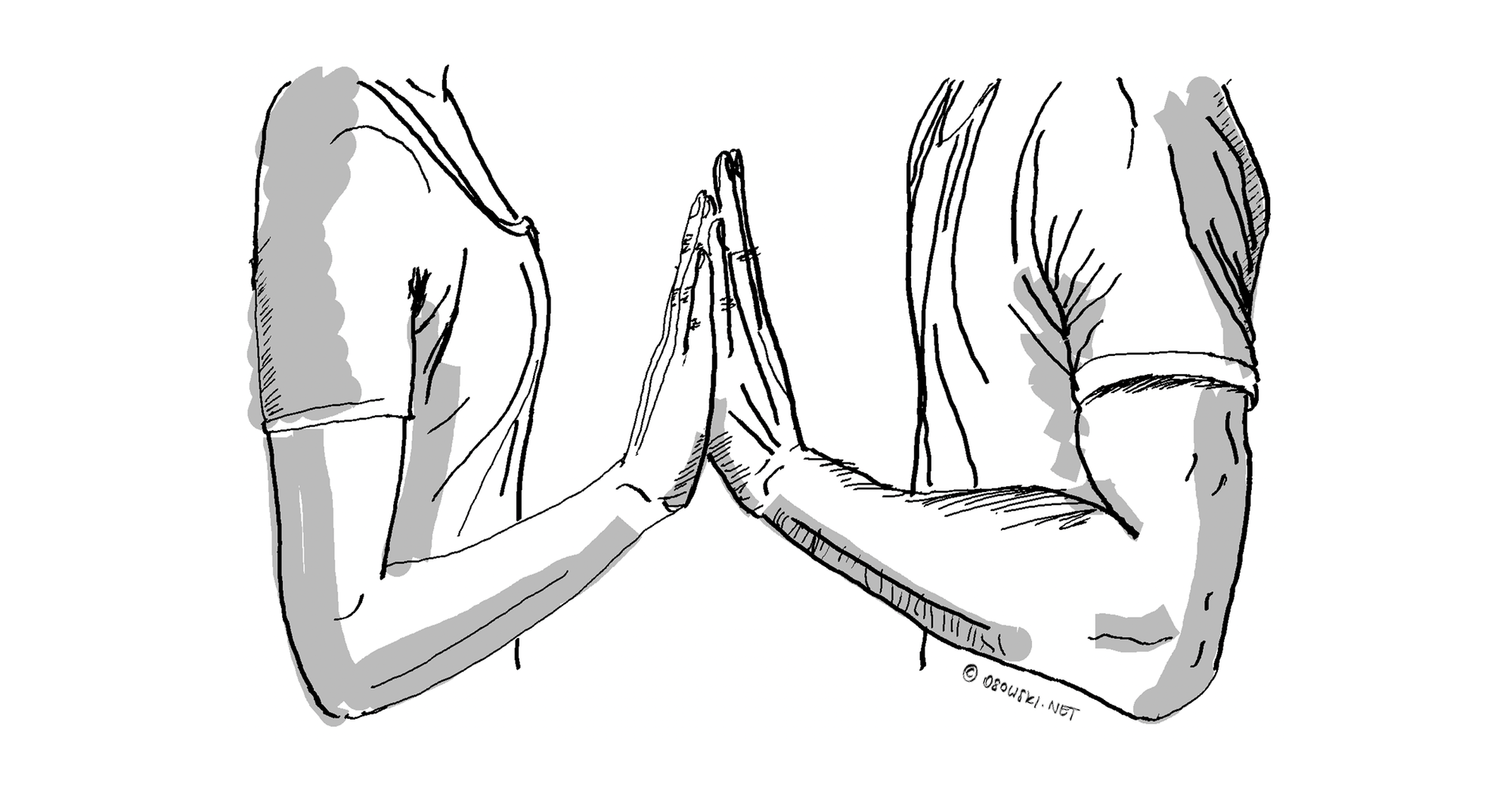

I used to be a competitive ballroom dancer. The most important lesson I took from dance into business is this: achieving results requires mutual pressure from both sides.

Here’s how it works: the partners stand facing each other, touching with outstretched palms. Both lean slightly toward one another, creating gentle pressure with their hands. Now they can feel each other clearly.

If one side eases up, they signal to the other that they want to step back. If instead they increase the pressure, it’s a way of saying they’d like to move forward. The same goes for directing the pressure left or right.

Pressure makes the pair steerable. Mutual pressure guarantees constant communication.

It’s the same at work. Subordinates’ resistance can make a boss reconsider whether the task they’ve assigned is really useful. Pressure from colleagues can keep us from being late to meetings.

Beyond the obvious, natural push from the organization and from your boss, there are a few other forms of pressure that I believe are worth feeling at work:

- internal pressure – motivation; appreciate those who, through their attitude, raise the bar for everyone.

- peer pressure – according to research ❸ the most important form; it defines what the team won’t tolerate, sets acceptable standards across all aspects of work, and is the main expression of organizational culture, with a decisive impact on quality and timeliness.

- resistance toward your boss – forces them to set valuable, achievable, and well-defined goals and tasks, consistently and with proper lead time.

- pressure from other teams – both from those working with us in a matrix (e.g. UX, accounting, compliance) and from those similar to ours (e.g. another development or sales team); it provides different perspectives and acts as a benchmark for our own results.

Healthy Pressure

Although I’m not his biggest fan, Steve Jobs beautifully described the value of clashing with one another at work. You can hear his famous metaphor of a product team as a “polishing drum” in the recording below.

Without mutual pressure, ideas, tasks, or results don’t get polished by multiple minds. They miss out on the benefits of “collective genius.” They don’t gain from the “synergy effect.” But that doesn’t mean we should be crashing into each other like pebbles in an old washing machine drum (sorry, Steve). Instead, especially if you’re not fond of clashes or you work in an environment low on openness to criticism, you can create a synthetic conflict using one of four popular methods:

- Devil’s Advocate – appoint someone whose role is to look for weaknesses in the proposed solution. The criticism becomes depersonalized – it’s now just part of the play, not a colleague attacking you. Psychologist Charlan Nemeth found that even a faked devil’s advocate increased consideration of alternative solutions by 61% ❹.

- Premortem – a method developed by Gary Klein where the team imagines the project has failed miserably and tries to explain why. This reframes criticism – from negatively “tearing down” assumptions to positively contributing to the exercise ❺.

- Dialectical Inquiry – the team splits into two groups that support divergent solutions or different assumptions. Options are debated, then one is chosen or synthesized. In a meta-analysis of 26 studies, dialectical inquiry led to better outcomes in 87% of decisions compared to single-plan consensus ❻.

- Six Thinking Hats – a method by Edward de Bono where team members adopt six distinct perspectives: analytical (facts), intuitive (feelings), negative (against), positive (for), creative (alternatives), and facilitative (moderation). This forces a comprehensive examination of the problem ❼.

None of the above can fully replace an organizational culture where people treat each other like adults and substance outweighs politics. But they can serve as a good workaround when that culture is missing – and as a foothold from which you can start building it.

Pressure by Design

Smart organizations have been building constant, mutual pressure into their structures for at least 2,700 years. Leaving aside the Spartan diarchy – where two kings ruled while constantly keeping each other in check (8th c. BC) – the most famous example is Montesquieu’s separation of democratic powers into executive, legislative, and judicial (1748). If you doubt its effectiveness, just notice how much it enrages authoritarian populists.

The modern organizational equivalent of this approach is Atlassian’s Product Triad ❽. In this structure, the team roadmap is co-owned by three specialists with differing perspectives:

- UX Designer – focus on user desirability: the solution must delight the user.

- Product Manager – focus on business viability: the solution must make sense for the business.

- Tech Lead – focus on technical feasibility: the solution must be achievable and scalable.

And if you believe your own wisdom is enough to balance all three of these perspectives single-handedly – read my piece Every Pro Has Its Cons again. This time with comprehension.

A 2012 meta-analysis also highlighted two aspects crucial for the effectiveness of structured friction. These systems work when they are limited and depersonalized. They turn toxic when there are no structural boundaries or conflict-resolution processes, and when they take on a personal character ❾.

Sparks Will Fly

At the same time, I don’t want to fool you into thinking you can have your cake and eat it too. Yes – focusing on better results instead of patting each other on the back can have a negative impact on your workplace relationships. Your job is to create pressure in the most skillful, positive way possible. The fact that you don’t yet know how to do it doesn’t change the reality that your team and product could benefit from it. And yes, there will sometimes be misunderstandings and accidents along the way.

Paradoxically, applying pressure can only happen in an environment that is truly safe – one with a mature boss and a confident team, where mutual respect among members is a given ❿. If your workplace demands a constant, uncritical smile and crushes assertiveness, treating feedback as an attack on someone’s dignity or as a personal insult – let’s not kid ourselves, there is no real sense of safety there.

I sincerely wish for all of us to be part of organizations full of healthy pressure – and leave you with John Oliver’s brilliant cautionary piece on what happened to Boeing once it stopped being one of them.

Sources

① “According to legend, Tsar Peter the Great ordered: ‘A subordinate in the presence of his superior ought to appear oppressed and embarrassed, so as not to embarrass the superior with his knowledge.’ Modern historians, however, note this decree is apocryphal.” – Provereno Media. (2021). Did Peter I really issue a decree that subordinates should appear bold and foolish before their superiors? Source: Provereno Media

② “The WHO Healthy Workplace Framework defines the foundations of a healthy workplace as including the physical work environment, the psychosocial work environment, personal health resources, and enterprise community involvement. It also emphasizes a healthy organizational culture characterized by trust, honesty and fairness.” – Burton, J. (2010). WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices. Geneva: World Health Organization. Source: WHO

③ “Of course, the best kind of accountability is peer-to-peer. Peer pressure is more efficient and effective than going to the manager…” – Patrick Lencioni, quoted in GTA University Centre. (2022). Creating a Culture of Accountability is Key to Success. GTA News. Source: GTA.gg

④ “Even when the role of devil’s advocate is only assigned, without genuine conviction, it still increases divergent thinking and the consideration of alternatives by 61%.” – Nemeth, C. J., Brown, K., & Rogers, J. (2001). Devil’s advocate versus authentic dissent: Stimulating quantity and quality. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(6), 707–720. Source: Wiley Online Library

⑤ “A premortem is prospective hindsight: imagining that an event has already occurred increases the ability to correctly identify reasons for future outcomes by 30%.” – Klein, G. (2007). Performing a Project Premortem. Harvard Business Review, September 2007. Source: Harvard Business Review

⑥ “In a review of 26 empirical studies, dialectical inquiry groups produced superior decisions in 87% of cases compared with consensus groups.” – Schweiger, D. M., Sandberg, W. R., & Rechner, P. L. (1989). Experiential effects of dialectical inquiry, devil’s advocacy and consensus approaches to strategic decision making. Academy of Management Journal, 32(4), 745–772. Source: Academy of Management

⑦ “The Six Thinking Hats method identifies six modes of thinking: White (facts), Red (feelings), Black (critical), Yellow (optimistic), Green (creative), and Blue (process control). It encourages parallel thinking and comprehensive analysis.” – de Bono, E. (1985). Six Thinking Hats. New York: Little, Brown and Company. Source: Little, Brown

⑧ “Atlassian product teams are run by a triad – a product manager, a design lead, and an engineering lead – who share equal accountability. The tension between their different perspectives ensures better decisions.” – Bowen-Bate, J. (2025). Strength through tension: in defence of the product triad. Mind the Product. Source: Mind the Product

⑨ “Task conflict can improve decision quality when it remains depersonalized and bounded, but it becomes harmful when conflict resolution mechanisms are absent or when it shifts into relational conflict.” – de Wit, F. R., Greer, L. L., & Jehn, K. A. (2012). The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 360–390. Source: PubMed

⑩ “Psychological safety describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves. It is the single most important factor in explaining team performance.” – Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. Source: JSTOR